Home towns have a rough time of it in fantasy and science fiction. The front-of-the-book fantasy map teems with inflammable beloved peasant villages, wrecked pastoral moon colonies, castles laid waste or inherited by cruel and unfeeling kings, roving players’ caravans devastated by attacks of Plot—you wouldn’t want to buy property in most main characters’ hometowns, is what I’m saying. This isn’t just a book thing, either. In Mass Effect, the player chooses one of three backstories for the hero, Commander Shepard: she can be an orphan from Earth, an orphan from space, or a kid (with parents! who, admittedly, never show up in game, but as a parent myself I appreciate the rep) who moved so much growing up that she doesn’t even have a home town, in a Reacher-esque ‘constant exile’ sort of way. Every Dragon Age I backstory prologue leads to a “Run Away, Simba!” moment. Luke Skywalker’s uncle and aunt end up extra crispy on Tatooine, and “there’s nothing for me here now.”

Now, this isn’t me pointing my finger and shouting “tropes!” in that Simpsons “NERD” voice. Sure, it’s possible to deploy these story beats cynically, but it’s possible to do anything cynically, except maybe sing “Total Eclipse of the Heart” at karaoke night. But the trope works for a reason. The loss of the home—the forced expulsion from a place of love and warmth and beloved constraint into a cold vast questing expanse—has profound biological correlation with the experience of birth, and it echoes all our other experiences of nest-leaving. Also, it’s narratively useful—comfortable people don’t go on many Adventures.

But I’m drawn to the return. To the moment the hero comes back home.

Homecomings are so rich. We see the hero, grown perhaps, or hardened, wounded, transformed—and we see the world they left behind. Maybe their old lives forgot them, or maybe they’ve been waiting. We experience that beautiful parallax so particular to prose: we see changes in how characters—old friends long parted, parents and children, lovers and grade school friends—perceive one another, the texture of memory, the gap between what they were and what they are now, through the stories they tell rather than through the transformations of their bodies as we perceive them. We come to know how the world has built them up and destroyed them, both at once, from inside. Homecoming is a moment of narrative possibility—a moment when the hero sees, or states most directly, what, and who, home is for them.

And who they want to be for home.

Here are five-ish SFF stories featuring momentous homecomings.

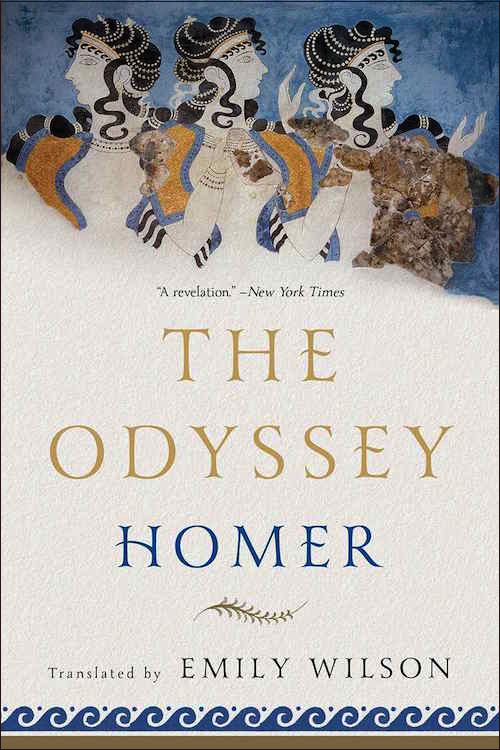

The Odyssey

I get this one for free, right? I hope so. To be honest I’ve always liked the Odyssey more than the Illiad. Part of the problem is that I adore Hector and Andromache and Astyanax, and Hector literally gets it in the neck. But I love the Odyssey in all its shapeshifting weirdness. There are moments and symbols of profound heartache and love, beats so elemental that it’s hard to imagine anyone coming up with them—the olive tree bed, the old dog recognizing his master in disguise, Penelope’s tapestry, Achilles’ message from the underworld—but the story doesn’t shrink from the fact of Odysseus’ absence, the toll it takes on his family, and the extent to which he brings the war home with him. Even as it codifies homecoming tropes for all post-Hellenic culture, it does not let homecoming be simple, or easy, or even final. The murdered suitors are not serial villains, though some of them try to kill Telemachus; they are also of Ithaca, and they have families and friends who mourn them, and seek vengeance. (If only the murdered maids and servants received as much!) Nor is return the end of Odysseus’ journeying, or his atonement. (As long as I’m here, shout out to Madeline Miller’s Circe, which, along with a bunch of other great stuff, has an all-time champion hard-but-true take on Odysseus’ homecoming, featuring plot elements from the parts of the epic cycle I don’t like to think about too much because they get in the way of my sentimental HEA desires for Odysseus and Penelope.)

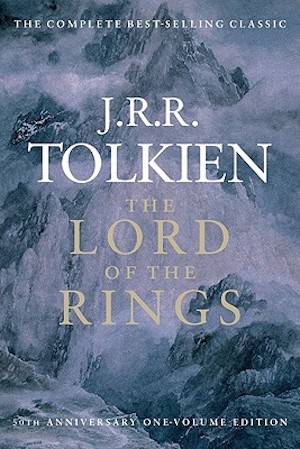

The Lord of the Rings, by that guy

I did not appreciate the Scouring of the Shire—in which the Hobbits return from their grand quest to find the Shire has been taken over by Saruman, and turned from an idyllic countryside into an industrialized gangster state— when I was a kid. It’s not, I think, that I didn’t want the Shire scoured. My issue was one of pacing and structure—Sauron is gone, the Great War is over, we’ve had our quest-companion leave-takings already, are we really going to have more plot now? But the Scouring makes the whole rest of the story real. Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin didn’t go on some kind of dream-voyage to wake up in a world unchanged: the Shire was transformed by the War of the Ring, and wounded. Once Frodo and Sam and Merry and Pippin and the other hobbits free the Shire, they begin the long work of healing together. The Scouring externalizes the wound of the Morghul knife in Frodo’s shoulder, the trauma of living in history. These days I wonder if there’s a bit of authorial mercy in that, if Tolkien understood that it would be easier for Frodo to live wounded in a wounded Shire and play some part in its healing than it would have been for him to live wounded in a Shire as blithe and unconcerned with the doings of the world as it was before he left. Also: without the Scouring, no mallorn tree.

The Game of Kings by Dorothy Dunnett

Lymond is back. Aside from the first line of Lord of Light, I can’t think of a first line that has done more for me—one of adventure fiction’s truly incandescent openings. Dorothy Dunnett, never one to make things easy on herself—or the reader—performs in The Game of Kings the extremely rare standing-jump homecoming: cold open with the homecoming itself, its impact and implications, and let the reader suss out the circumstances and history of the absence from context and reaction shots. This is how we meet Lymond—scapegrace murderous catty snark-monster Scottish ninja polymath—after a decade’s exile, and the world and his family shaken root and branch by his return on a mission of–well, at first it’s not exactly clear. Does he seek revenge for his own exile, on his brother and his country? Reconciliation with his family? Justice? Just to make a quick buck? It depends on who you ask, and whether they’re telling the truth. Lymond himself is not forthcoming. I often wish the first hundred pages of Game of Kings were an easier lift when it comes time to recommend the book—it was Dunnett’s first novel, I don’t think she realized that most readers aren’t up for big chunks of untranslated medieval French—but as always her work is a master class in perspective and assumption, and a riveting story about home and family and our ties to both, that bind both ways.

Planet for Rent by Yoss

This is the loosest fit on the list—it’s a mosaic novel for one thing, rather than a narrative structured around a single dramatic instance of homecoming—but it’s rare to see the question of home raised with such care or passion, or held up to the light at so many striking angles. Yoss envisions the post-Contact future of a backwater Earth not (altogether) conquered (yet) but pervasively subordinated to an alien cultural and economic hegemony. What does home mean when those in power sell it out from under us? When we sell ourselves (our bodies, our deaths, our dreams) to achieve something we’ve been told is freedom, or consequence? What does it mean to love a place that’s being torn apart around you? To love a place you feel you absolutely must escape in order to survive? The characters throughout Planet for Rent strive, fight, create, fail, and sometimes even succeed in the context of a field of colonization and oppression that works to define them in ways both obvious and subtle. And—look, all this might sound pretty theoretical and abstract to you but by God this book is pacey. Reading it feels like you’ve hooked your imagination to the tow cable of a rocket ship.

Queen of the Night by Alexander Chee

I guess this is another loose play but once I started thinking about the book in the context of homecoming I wasn’t able to stop. Queen of the Night is a story of coming home not so much into a place (though it does come back around, in the end) as into our own memories, our own lives. We open with Lilliet Berne the great diva of the opera stage, untouchable at the top of her game, darling of Paris society—a woman who has parted ways with her past for many reasons, including: to secure her present. When Lilliet’s confronted with a manuscript with striking echoes of her own (secret) life story, she works through her own memories to learn who and what has come back to haunt her. Chee accomplishes a gorgeous doubled effect, through which our experience of Lilliet’s memories and life story flesh out the social and emotional world of her present until the stunning and charismatic character of the novel’s first scenes becomes an achingly real and familiar person, without losing her glory. This homecoming is destructive, as so many are—but it promises, too, an honest resurrection.

The Saint of Bright Doors by Vajra Chandrasekera

The Saint of Bright Doors is a great example of the rarely seen double-homecoming. Our protagonist Fetter was raised by his mother as a mystical assassin, a weapon aimed at his father’s heart. But as a teenager, he ran away to the big city, made a life for himself, joined a support group for other former Chosen Ones dealing with what happened when they decided not to be the agent of this or that god or apocalypse. It’s a brilliant, expansive book, with a lot to say about home and love and time and identity and urban space—and it troubles this central question of what’s home, and can we ever go back. What’s the home to which Fetter might return? Is home his mother’s compound, and the destiny from which he fled? Is home his adopted city? Is home a place, a time, a person? What happens to home when that time is gone? Where does it go?

***

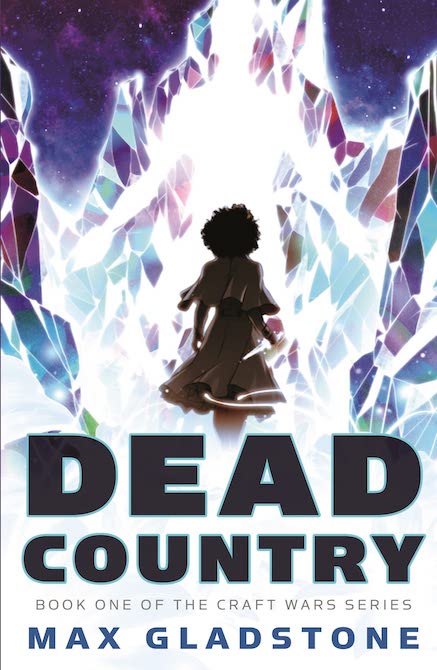

And, if I may be so humble as to submit: my novel Dead Country. Tara Abernathy, big city necromancer (who you may remember from Three Parts Dead and the other novels of the Craft Sequence), returns to the small town she left behind. She’s come to bury her father. But as dark forces gather in the Badlands, Tara finds herself defending the town of Edgemont, side by side with the same folks who chased her out with torches and pitchforks years ago—as she struggles to teach and protect another small-town girl with a knack for the sorcerous Craft. It’s a story about homes and the extent to which we can know them—about the ways folks change, and the ways we do, and what if anything endures. And, you know, it’s a story about the end of the world.

But aren’t they all?

Buy the Book

Dead Country

Hugo, Nebula, and Locus Award–winning author, MAX GLADSTONE, has been thrown from a horse in Mongolia and once wrecked a bicycle in Angkor Wat. He is the author of many books, including Last Exit, Empress of Forever, the Craft Sequence of fantasy novels and, with Amal El-Mohtar, the viral New York Times bestseller This Is How You Lose the Time War. His dreams are much nicer than you’d expect.